Back in the days when the digital revolution was still sci-fi fiction and cameras and film stock were the only devices available, filmmakers used to rely heavily on in-camera effects, with techniques like stop trick, stop-motion, miniatures and multi-exposures: all the visual effects were created using one single film stock and post-production was just a mirage.

Sometimes in the 1930s though, Linwood G. Dunn started to deploy an Optical Printer to produce visual effects separately, without the in-camera limitations. Enabling filmmakers to re-photograph one or more film strips, Optical Printers are devices linking a movie camera and one or more projectors and were originally used to copy and reduce the size of the prints.

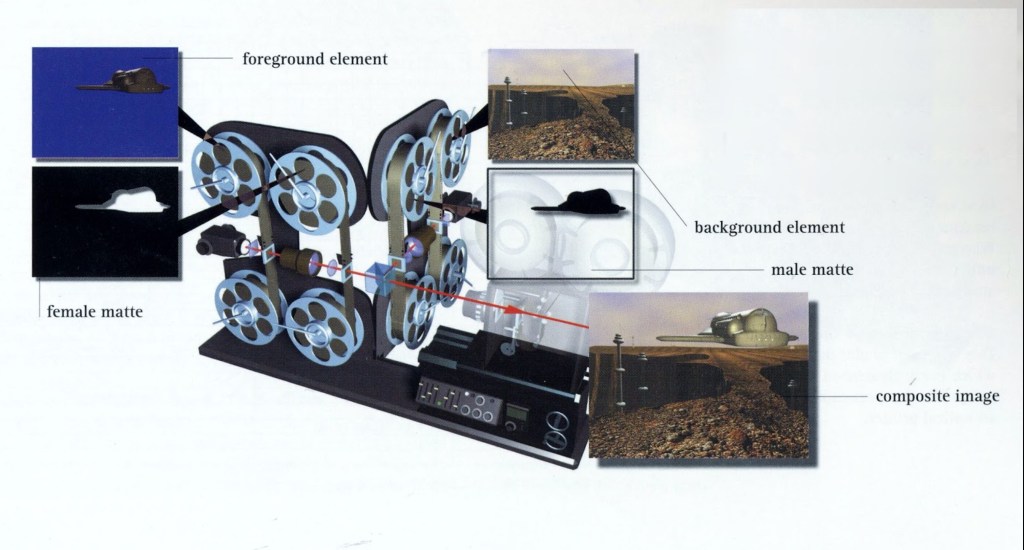

Expanded and improved over the years, they were largely used until the 90s, when the results achieved by computers and digital compositing surpassed them in quality and efficiency. But not before producing some world-wide famous blockbusters like Star Wars (1977), RoboCop (1987), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) and The Addams Family (1991). The concept behind the Optical Printer is simple: there is a live-action footage filmed on set (also called “plate”) and a separate footage with the new element (miniatures, cartoons etc.) to be combined and merged over. The live-action footage would be in the background and the new element in the foreground. Both films are also equipped with a matte, male matte for the background and female for the foreground, which provide information about the transparency and the opacity of each frame: the white area is visible and the black area invisible.

With the advent of the computer era in the late 1970s, the white and black matte concept was eventually translated into digital by Alvy Ray Smith (co-founder of Lucasfilm’s Computer Division and Pixar) and Ed Catmull (co-founder of Pixar and former President of Disney Animation Studio), and renamed Alpha channel (like the Greek letter 𝛼). The digital Alpha channel could control and adjust the transparency interpolation of two images per pixel, providing a major boost to the computer graphics industry.

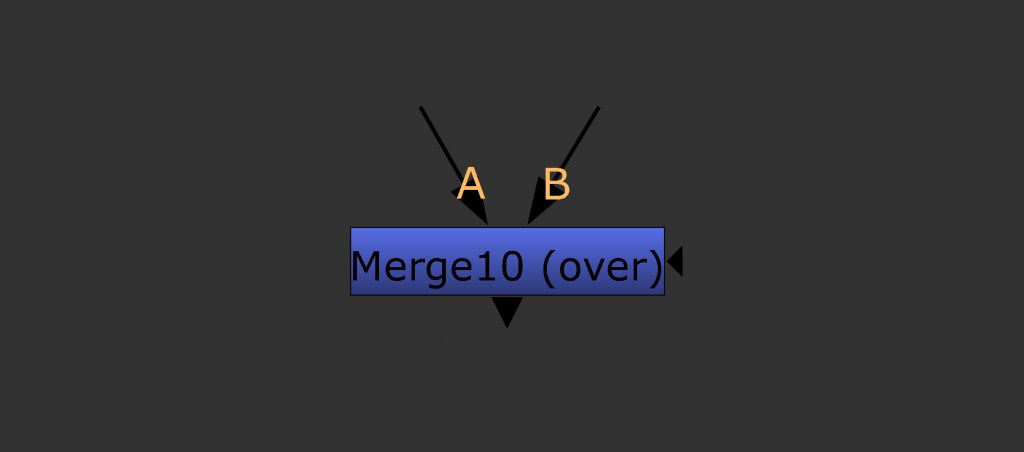

At the end of the 1990s the process of combining a background image or video with a foreground element was almost completely digital and renamed digital compositing, but the original concept and ideas are still valid and used in tools like the Merge node in Nuke: a simple gizmo that allows you to merge a background element with a foreground with two inputs.